A common association with barbershop is four creamy guys with matching pin-striped suits and fine straw hats. This assumption was made very clear to me when I read HALO’s first review from our a capella contest, the critic calling it “whitest musical style there is,” wondering what the four of us were doing singing it. Even still, people have also asked us why we chose such “white” songs to perform for our shows and competitions.

The thing is, they didn’t sound “white” to me. “Cheek to Cheek,” our first chart, is perhaps a square arrangement, but it helped us to lock sounds and move easily together– and it was the harmonies that still felt like home to us.

I was not at all acquainted with the existing world of barbershop before the Lewellens came into my life and Epic was born– but what I thought of pertaining to the music as a genre was more along the lines of a few black guys kickin’ it, making up chords, harmonizing their favorite tunes and improvising others at random. I heard the professional renditions of the tightly-voiced jazz harmonies of male voices in groups like Take 6, and even Boys II Men, while the more city street and even “folksy” images were born of their portrayals in movies like Polly, starring Phylicia Rashad and in my own life, saturated in music-making experiences present in both our churches and under our own roof.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Elq9MYJkYIc

My sister and I grew up listening to and singing lots of Motown and girl groups, as was the standard pastime under our very musical parents’ influence. We would often play around with harmonizing songs while listening to the radio or even just playing with our Barbies (they, too, sang in contests and pageants, naturally). improvising many a tune when we younger than 12, simply singing about stuff we were excited about doing. It was just… how we rolled. So when I started to listen to and sing the arrangements very specific to the barbershop genre– songs I was familiar with with harmonies that I’d heard and sung all my life– I just thought: oh, I know ’bout this.

So perhaps you can now imagine my surprise that someone would ask, “why are they singing that ‘white’ music?” Where did this assumption come from if I felt so connected to this music in my own family’s culture? So much of our music making is at the root, family-oriented, after all– so it stands to reason that those roots aren’t reflected as prominently in the realm of the spotlights, where the music certainly was performed at the very finest places and on all sorts of recordings. Just not as much by us. How did a capella jazz singing become dissociated from black culture under the label of “barbershop?”

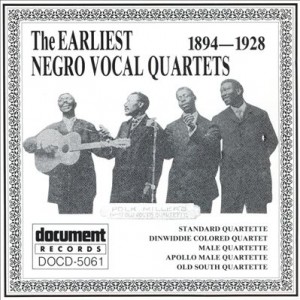

While distant anecdotes and vague recollections may not serve to restore this sense of identity, there fortunately is existing documentation that traces the origins of what we call barbershop back to the black communities. In Lynn Abbott’s article, “Play That Barbershop Chord: A Case for the African-American Origins of Barbershop Harmony,” Abbott references the recreational facet of ensemble singing in the black neighborhoods and places of business. “Sing parties,” he says, were social gatherings conjured by blacks because they couldn’t attend public concerts. While the segregation laws may have influenced the “purpose” for our parties, singing together was part of our way of being before Africans were even brought across the Atlantic. This communal singing is a social activity that is very much a part of our identity as a people and one of the very few traces of cultural identity we managed to hold onto when slaves were forced to divorce from them all, lest we believe that we were, indeed human. But even when not all of our musical expressions thrived, (drumming was banned in many slave communities) our singing survived with songs centuries old still sung today.

Abbott then briefly references minstrel troupes as a place wherein black men performing as quartets was cultivated, then continues in describing the social context in which this style continuously thrived. Though the real-life music making and social culture of African Americans post-slavery speaks more to the soul of the people singing it, the caricatural representation of it in minstrel shows also speaks to its origin in the black community.

Pictured above: The Georgia Minstrels; first black minstrel troupe, formed in 1865

Minstrel troupe quartets were performed in black face, even by actual black men; these circus acts were parodies of black culture, characterized by goofy, “cooning” lazy slaves who sang songs together to express their happiness and contentment with their station in life serving the white man. The ways of life blacks had adopted just to manage surviving (while many spirituals speak to the longing to escape this life) were thus taken out of context in order to advocate the assumed decency of slavery in the late 19th century.

As for the original “babershop,” Abbot then gives account of the actual men’s parlor scenes where black men gathered for gentlemanly camaraderie and would often sing together. Other parlors in the city were hot spots for vaudeville musicians to gather and top shelf performers would sing together and entertain customers while they threw down a few drinks. Joe Sarpy’s Cut Rate Shaving Parlor was “Headquarters for Dining Car and Railroad Men” and Dewberry’s Shaving Parlor and Social Club were known spots where good musicians gathered. A couple of well-known quartets of the time were Callender’s Minstrels and Mills Brothers, who also I nfluenced other quartets, including Southside Quartet.

This vintage sound was also present in women’s singing, though because they wouldn’t gather in barbershops for their social singing or performances, they weren’t part of what was pigeon- holed as the barbershop genre. Women sang in family groups and would perform in clubs and the famous (of the time) Rabbit’s Foot Company, but the names of these groups are even more obscure, save the Dandridge Sisters– who would have remained just as unsung had it not been f for the stardom and ground-breaking career of their lead singer, Dorothy– but that’s another blog for another day.

Check in for “Part 2” of this discussion… HALO is going to have lots to talk about as we embark on upcoming performing opportunities and endeavors of connecting with others to reconnect with this part of our musical heritage. But for starters, a closer look at that heritage will be the groundwork of our inspiration. Thanks for reading!

Heard some talk about cf6886, anyone tried it out? The site looks decent enough, wondering if it's worth a punt. Let us know your experiences! cf6886

Wim222... name's catchy, I'll give them that. Standard stuff overall but hey, options are good. Try it, maybe you'll dig it! wim222

Yo, 595betvip! Just tried it out. Got a smooth experience. Definitely worth checking out if you're looking for something new. Gotta say, I wasn't disappointed! Check it out here: 595betvip

Having issues logging into Sv388? The sv388dangnhap site provides alternative login methods. Check here: sv388dangnhap

Heard some buzz about ph222casino.com. Gave it a spin, and honestly, not too shabby! Good selection of games and the payouts are legit. My take is you should check it out with this link: ph222casino

Playing io, my dudes! Heard good things and gave it a shot. So far, so good. Give it a whirl! Check it out: playing io

Mobile betting is where it's at. JJbetapp looks sleek and easy to use from what I've seen. If you're on the go, this could be the app for you. Download it here jjbetapp.

Just tried hm888 and gotta say, the signup was smooth. They've got a good range of stuff to bet on. Deposits were quick too. Give it a whirl if you're after some quick action. hm888

Hey, 3patticrownapk is pretty awesome! It is fun to play with friends. It’s exciting and the graphics are great. Try it out: 3patticrownapk

Alright, checked out gembetapp. Easy to use and everything seems in its place, worth a quick look. Check it out at gembetapp

Need a good place to catch the ga choi c1 tv action. Gonna try gachoic1com.com and hope they have the best streams! Wish me luck! ga choi c1 tv

456bet1's got a good selection of games. Nothing crazy, but solid and reliable. Might be worth a look at 456bet1.

I’ve been poking around 52bet9 lately. Seems pretty solid. Good promotions, too. Give 52bet9 a shot!

Checked out lasvegascasino.info – lots of info on Vegas casinos! If you're planning a trip or just dreaming about one, this is a good resource. Check it out for the lowdown: lasvegascasino

Sup, had a blast tonight on evotaya777! Won a bit, lost a bit, but had fun, which is the point, right? Give it a whirl: evotaya777

Okay, so Crashercasino… it's a bit of a rollercoaster! Won some, lost some, you know how it goes. But the vibe is fun, and they have some cool promotions going on. If you're feeling lucky, give it a whirl! crashercasino

Alright, bet9096! Just checked it out and I gotta say, not bad! Seems like a decent spot to try your luck. I'm giving bet9096 a shot this weekend. Wish me luck!

Hey folks, hopped on ph364login the other night. The login was smooth – no hassle. Games are pretty standard, but the overall experience was good. Give it a try if you're looking for something new. ph364login

Gave ubet95casino a whirl. Not too shabby, got a decent selection of games. Took a bit of spinning and it seemed alright. Have a look for yourself: ubet95casino