Continuing this article, Abbott then observes the emergence of the white origins theory of barbershop singing, rooted in the writings of three musical scholars in particular– Sigmund Spaeth, C.T. “Deac” Martin and Percy Scholes– whose quotes on the subject ranged from the claim that barbershop singing was a treasured and peculiar art of the Negro, to barbershop’s true heritage a vague unknown. Spaeth was one even to reference “barber’s music” of the renaissance the likely origin,likely to have been “strummed on the lute” by men in ruffled shirts. Though any reasonably educated musician would be hard-pressed to conjure the styles of the madrigal a closer relation to the tight harmonies of barbershop than traditional spirituals and the jazz of New Orleans, the persistent agenda of dissociating an adopted art form from African American culture made such far fetches worth the reach. It stands to reason that the same author, in another work entitled They Still Sing of Love, apparently dismisses the position he took in the above writings published as Barbershop Ballads as rather devoid of much scholarly substance and claiming instead that barbershop was more likely to have emerged from the shops owned by black men in Jacksonville, who would harmonize and improvise the close chords for which the style is now known.

SPEBSQSA (Society for the Preservation and Encouragement of Barbershop Quartet Singing in America) was founded in 1936 in Tulsa, OK and perpetuated the theory of barbershop’s origins in European culture through articles in their magazine, The Harmonizer. An organization exclusively for white men, any sense of roots in the black community of the music they were singing were rather completely disowned. Deac Martin, principal spokesman of the organization from his time joining in 1941 to his death in 1970– who once was forthright in acknowledging the barbershop style of a capella singing as belonging originally to African Americans– states later in his book, Keep America Singing, that as much as the human impulse to sing likely began as chants of “savage” tribes, the beginnings of barbershop are “impossible” to pinpoint. Abbott continues to examine a variety of perspectives among white scholars of the essence and origin of barbershop quartet singing, with some authors who observed with a sort of reverence its connection to spirituals and the social setting of the black barbershops in the country and the city, while others alluded to those beginnings in skits and vaudeville acts.

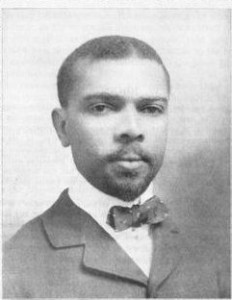

James Weldon Johnson– the author, educator, lawyer and musician who wrote the lyrics to the African American national anthem, “Lift Every Voice and Sing” comments on the origins of African-American music in barbershop singing in Book of American Negro Spirituals, published in 1925. A quartet singer himself with the Atlanta University Quartette, he describes the lineage of what we know as barbershop singing, stating “…it is, nevertheless, a fact that the ‘barber-shop chord’ is the foundation of the close harmony method adopted by American musicians in making arrangements for male voices. ‘Barber-shop harmonies’ gave a tremendous vogue to male quartet singing, first on the minstrel stage, then in vaudevile, and soon white young men, where four or more gathered together, tried themselves at harmonizing.” This argument does not even appear to be for the purposes of refuting “white” origins as the theory, but rather perhaps the European/Renaissance facet of that claim, having described its founding musicians as American, not as black. The subsequent statement, however, makes very clear that white men started to make this music after minstrel performers made it popular.

James Weldon Johnson

As an activist, his not specifically asserting that those American musicians were black musicians may even indicate its presumed obviousness to the intended readers. One may also take note of Johnson’s use of quotation marks over the term “barbershop” as a description of the style. Its organic and improvisatory style of expression, for those who were producing it, perhaps did not lend itself to such a limited and limiting label as a genre.

The question remains, perhaps: why does any of this matter? For some, the extent of this discussion of historical perspectives and accounts– which here is really only glazed over for the purposes of putting the HALO perspective into context– may seem surprisingly extensive. David Wright presented extensively on this very topic, concluding for listeners that:

- Understanding the past allows us to move forward

- The style of barbershop is broader than the community and the outsider has come to assume.

- The genre deserves more presence in the history and performance of jazz.

- The barbershop community must work toward breaking down racial barriers. (Take some time to delve into his examination of this history, if you haven’t already!)

Yet for me– for us– recognizing the roots of “barbershop” singing matters to and for the African American community. Music is part of cultural identity. From the beginnings of slavery of Africans, through the Jim Crow laws of the south, and the struggle of the Civil Rights movement, we were robbed of so much of this identity for ourselves– given instead a degraded and grossly distorted image of who we are. Since then, much of that distorted image has dissipated into but a phantomized recognition of our traditions, from which we may dissociate ourselves in effort to move past the stereotypes and evolve into self-actualized individuals. But our music represents the truth of who we are and who our forefathers were. Embracing this piece of them brings back missing pieces of ourselves as the self-actualized individuals we strive to be.

And once again– this is where HALO comes in. Here is this music we recognize and viscerally identify with, and here we are, the first group of all black women to compete with it in the community where many once said that people like us did not belong. In 1941, a quartet of African American men, The Grand Central Red Caps Quartet, won a regional contest sponsored by SPEBSQSA. However, they were denied the right to compete at the national level because they were black. Much to their credit, Alfred E. Smith and Robert Moses resigned their administrative postitions in protest to this decision, indicating both a recognition of barbershop’s cultural roots and its unique opportunity as a vehicle for social progress. The Barbershop Harmony Society has since issued a formal apology for this exclusion in the May/June 2015 issue of The Harmonizer. And true to the form of this very gradual progress, HALO is the first quartet to venture past that former barrier since then in competing on Harmony, Inc.’s international stage in 2015– a whole 74 years later. Given the proximity of timing, perhaps the time has come to re-examine our collective perspective of this music.

Listening to the vintage recordings of these quartets and reading peer-reviewed scholarly articles that account of musical traditions that felt familiar to me since I began this hobby helps to validate my visceral sense of connection to this music as part of my identity as an African American woman. Most of us may never know the original homes or names of our African ancestors before they were brought across the Atlantic. But what was passed on was our unique tradition in connecting and socializing with spontaneous singing– and that life, color, and improvisatory rhythmic quality rings like a song of our long lost native tongues when we hear people of all kinds joined together to sing those barbershop chords.

Hallo, Ihr Blog ist sehr erfolgreich! Ich sage bravo! Es ist eine großartige Arbeit geleistet! 🙂